What does it mean to be a curatorial killjoy?

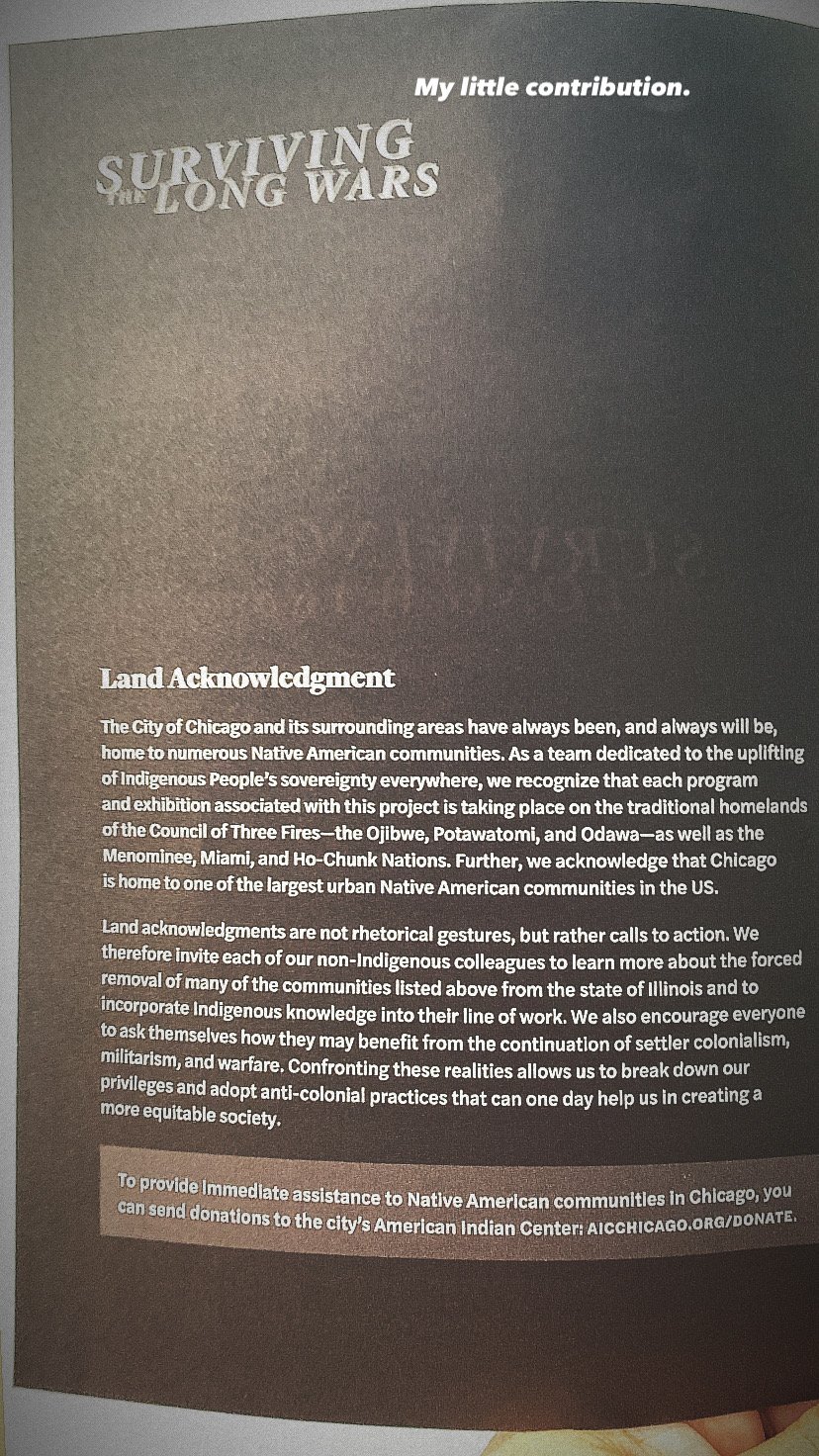

In 2019, after a challenging year working as a postdoctoral researcher/co-curator at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, IL, I embraced the moniker “curatorial killjoy.” This term resonated with me because during that time, I witnessed a consistent pattern of the institution seeking collaborations with Native communities that primarily served its own vision of decolonization, rather than genuinely addressing the needs and aspirations of Indigenous Peoples.

As a first generation scholar, my family has endured the devastating impacts of boarding schools and other forms of state sanctioned violence. Navigating the intergenerational trauma associated with these events, I also had to navigate Western educational systems that were not designed to support my lived experiences or existence. Recognizing the privilege I held in my position, I took it upon myself to publicly and internally call out behaviors that hindered meaningful collaboration. I voiced concerns about how white supremacy was being reinforced even in the pursuit of decolonization and advocated for change while highlighting the personal harm I experienced throughout the process. Unfortunately, this work environment took a toll on my mental health, affecting other aspects of my well being.

As I transitioned from graduate school into the professional world, I initially believed my strong voice alone could single-handedly effect monumental change. While I take pride in the advocacy work I undertook during that time, I have since learned the importance of meeting people where they are and approaching issues with less reactivity and more understanding. Although this institution failed to take my needs seriously and never fully acknowledged the challenges I faced, I have since found more receptive and caring working environments where I have been valued and respected.

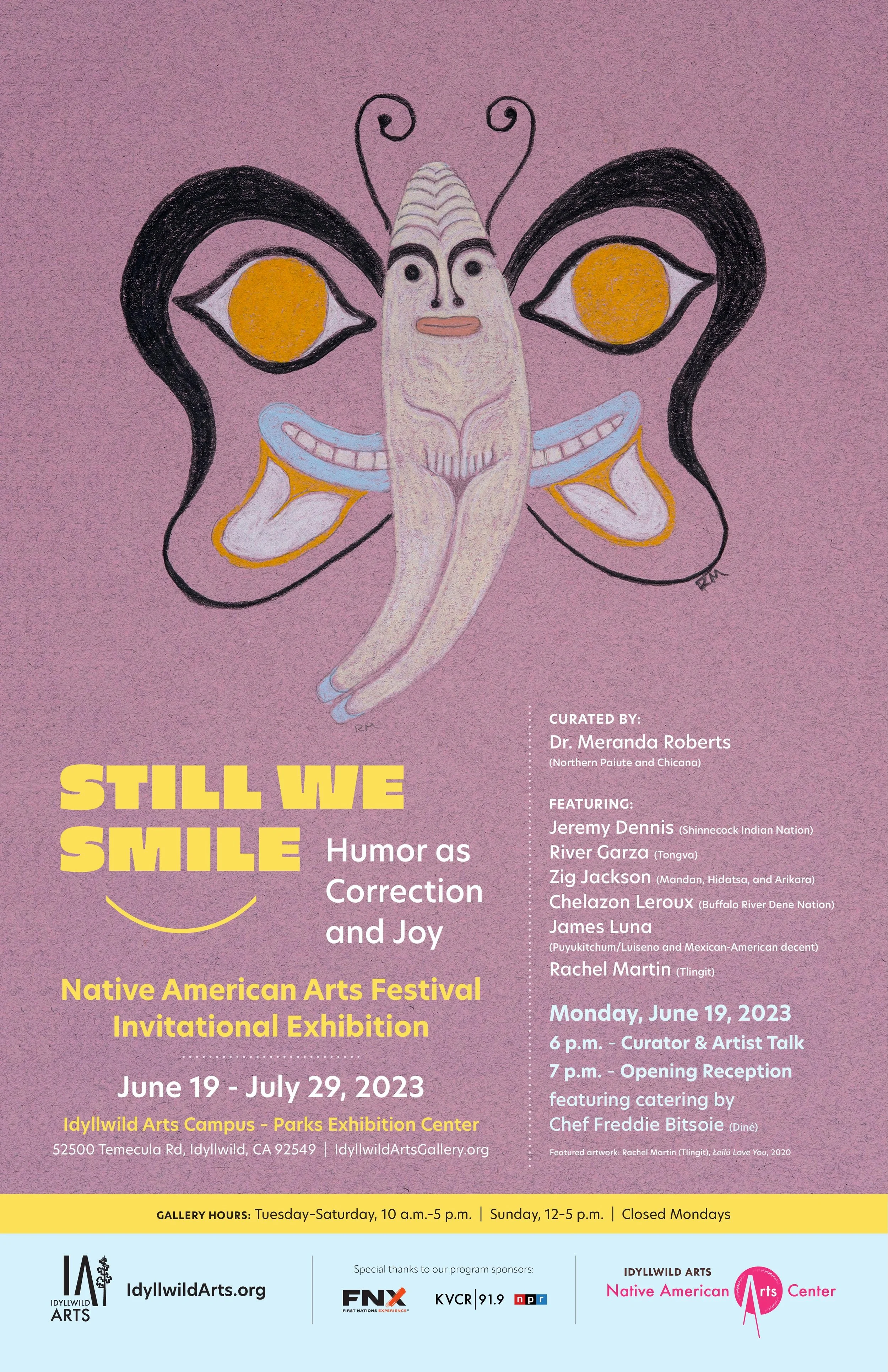

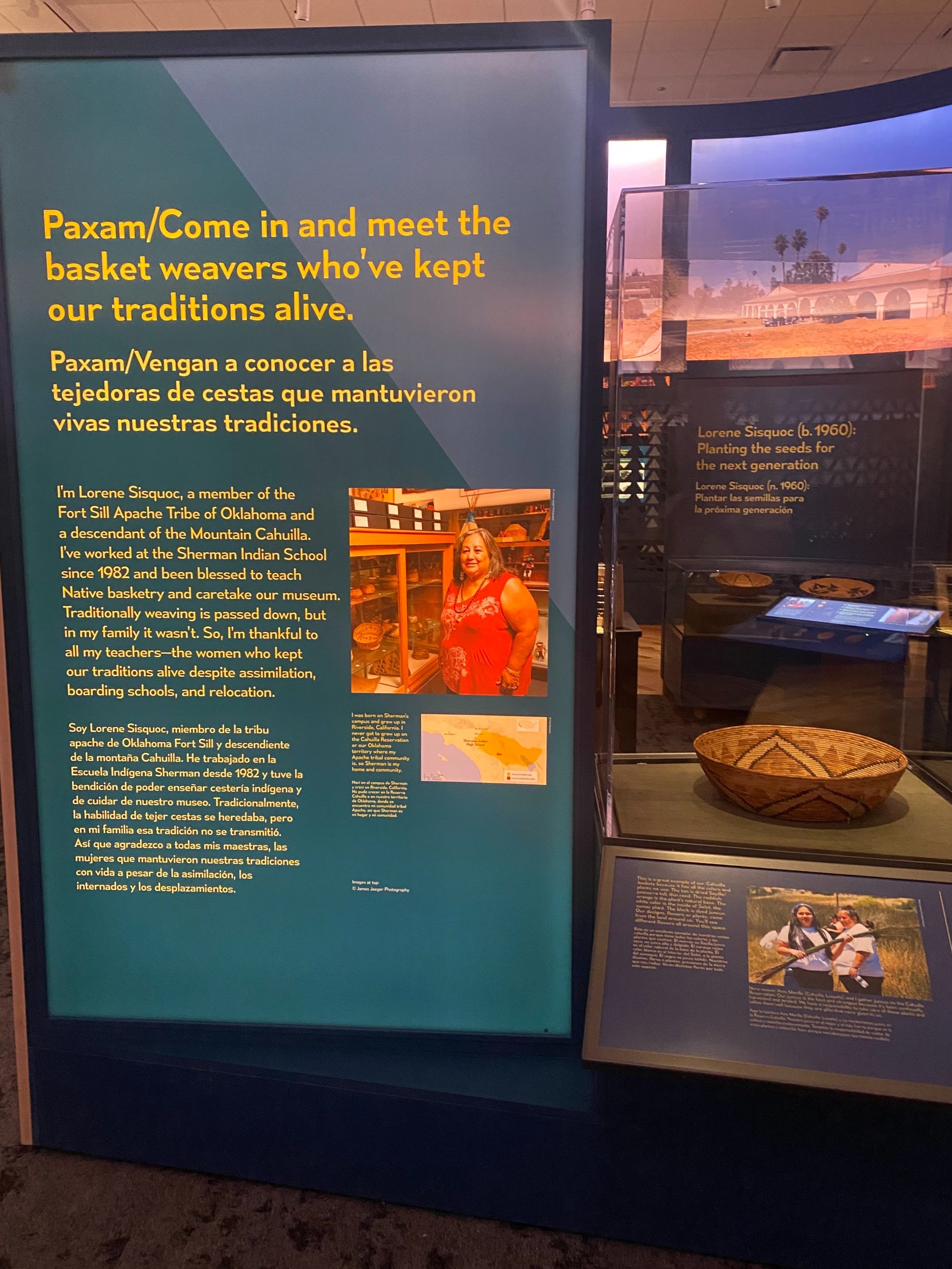

Through this experience, I gained invaluable insights into curating exhibitions that are grounded in care and mutual respect. I have come to understand that my role as a curator is not to tell a story from my own perspective, but to center Indigenous methodologies that prioritize community wants, needs, and desires. While I do not have the ultimate authority to speak for all Native People and their histories, I am committed to creating exhibitions that foster beautiful relationships and tell stories that the community wants to have told. My duty as a curator is to think of the next generation of Native museum workers and collaborators, and to pave the way for a more seamless and inclusive working environment. My curation tells a story….